Think Docker! Think Security!

Docker allows you to completely abstract the underlying operating system and run your app across multiple platforms (local machine, cloud or on-premise data centre) as long as the destination has the Docker runtime (Docker daemon) running. With Docker, the Continuous Delivery philosophy Build once deploy anywhere really comes to the fore. You build your binary artifact as a Docker image that includes all the application stack and requirements once and deploy the same image to various environments. This ensures the binary is built once and the same source code is promoted in subsequent deployments, allowing agile, continuous application delivery.

I have been using Docker for local development, testing and for running apps in production. Docker is pretty swift to get started with, allows rapid app development, setting up builds and running tests in a repeatable and consistent manner. You can get an application running on your local machine with all its dependencies (web servers, databases) in fairly quick time. Does that mean you ship your machine to production? Probably not! Because you are working with the Docker abstraction, do you need to worry about any underlying security risks, is it all taken care of or should you even care?

The basics

Docker is a virtualization technique used to create isolated environments called containers for running your applications. A container is quite like a VM but light-weight. It is a bare minimum linux machine with minimum packages installed which means it uses less CPU, less memory and less disk space than a full blown VM. Containers are more like application runtime environments that sit on top of the OS (Docker host) and create an isolated environment in which to run your application.

At the very basic level Docker uses the resource isolation features of the Linux kernel such as Namespaces and cgroups to create the walls between containers and other processes running in the host.

-

Namesapces control what processes can see. They allow resources to have separate values on the host and in the container; for example PID 1 inside a container is not PID 1 on the host. However not all resources that a container has access to are namespaced i.e they are not isolated on the host and in the containers. Containers running on the same host still share the same operating system kernel and any kernel modules.

-

cgroups (abbreviated from control groups) control what processes can use by limiting and isolating resource usage (CPU, memory, disk I/O, network, etc.) for a process.

Linux Security Module is another layer of protection that sits on top of namespaces and cgroups.

AppArmor can control and audit various process actions such as file (read, write, execute, etc) and system functions (mount, network tcp, etc). Again, while running a docker container you get a sensible set of defaults:

- Preventing writing to

/proc/{num},/proc/sys,/sys - Preventing mount

SELinux provides a mechanism for supporting access control security policies. Uses labels. Defaults for running docker include:

- Gets access to everything in

/usrand most things in/etc - To give more access: relabel content on the host

- To restrict access to things in

/usror things in/etc: relabel them

Seccomp is another security facility in the Linux kernel that allow an application to define what syscalls it allows or denies. Docker’s default seccomp profile is a whitelist which specifies the calls that are allowed. Running docker by default

- Prevents ~150 uncommon or dangerous syscalls

Capabilites are a set of privileges that can be independently enabled or disabled for a process to provide or restrict access to the system. Removing capabilities can cause applications to break, therefore deciding which ones to keep and remove is a balancing act. Docker containers run with a sensible subset of default capabilities, e.g. a container will not normally be able to modify capabilities for other containers. Apart from the capabilities removed by default you can remove or add capabilities while running a container.

Security challenges

So what sort of security issues should you be worried about that could affect apps running inside containers? I was at a GOTO conference in Stockholm earlier in the year and Adrian Mout speaking on Docker security highlighted some security issues mentioned below. The following is not a comprehensive list but one that should get you thinking.

-

Kernel exploits: The kernel is shared amongst all the containers and the host. A flaw in the kernel could be exploited by a container process which will bring down the entire host.

-

Denial of service: All containers share the kernel resources. If one container manages to hog kernel resources like CPU, memory or block I/O, it can starve the other containers on the host for resources, resulting in a denial of service attack.

-

Container breakouts: Running as root on the container means you will be root on the host. Therefore you need to worry about escalated privileges attack where a user can gain root access on the host due to a vulnerability in the application code. If an attacker gains access to one container that should not allow access to other containers or the host. Therefore it becomes important to run your container with restricted privileges.

-

Tampered images: You need to be sure that the image that you are running is from a trusted source and not from an attacker who has tricked you. The images that you run should also be up to date, scanned and without any known security vulnerabilities.

-

Secret Leakages: Secrets for your applications (like API keys and Database passwords) need to be protected from falling into the wrong hands. You need to be very careful before putting these as plain text in source code; for example in a Dockerfile. Once the secret has made it into the Dockerfile, even if you remove the secret later, an attacker can still retrieve it from the history of the Docker image built from the Dockerfile. Ideally using a secret vault for storing application secrets and allowing restricted access to the secret vault serves as a secure mechanism to distribute secrets.

Mitigations

Having gone through key Docker security issues, lets look at some ways to prevent them. CIS Docker Benchmark provides an elaborate list of docker security recommendations. Defence in Depth is a common approach to security that involves building multiple layers of defences in order to hinder attackers. The following mitigations are based on securing the host, container and image in a container based environment.

Host and kernel

-

Use a good quality supported host system for running containers with regular security updates. Keep the kernel updated with the latest security fixes. The security of the kernel is paramount.

-

Apart from updating and patching the kernel, it might be worth considering running a hardened kernel using patches such as those provided by grsecurity (https://grsecurity.net/) and PAX (https://pax.grsecurity.net/). This provides extra protection against attackers manipulating program execution by modifying memory (such as buffer overflow attacks).

Run containers with

-

Minimum set of privileges (non admin). When a vulnerability is exploited, it generally provides the attacker with access and privileges equal to those of the application or process that has been compromised. Ensuring that containers operate with the least privileges and access required to get the job done reduces your exposure to risk. A docker container runs as root by default, if there is no user specified. Create a non privileged user and switch to it using a

USERstatement before an entrypoint script in theDockerfile. -

Limited file system (Readonly access). Prevents attackers from writing a script and tricking your application from running it. This can be done by passing

--read-onlyflag todocker run. -

Limited resources (CPU and memory). Limiting memory and CPU prevents against DoS attacks.

docker runprovides options-mand-cfor setting the memory and cpu requirements respectively for running a container. -

Limited networking. By default containers running on the same host can talk to each other whether or not ports have been explicitly published or exposed. A container should open only the ports it needs to use in production, to prevent compromised containers from being able to attack other containers.

-

No access to privileged ports. Only root has access to privileged ports, so if you’re talking to a privileged port you know you’re talking to root.

Docker images

-

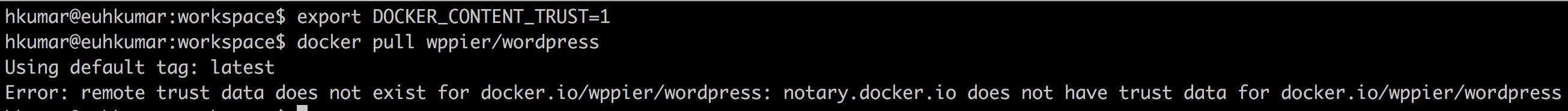

Only run images from trusted parties. Control the inflow of docker images into your development environment. This means using only approved private registries and approved images and versions. As of Docker 1.8 a new security feature was implemented called Docker Content Trust. This feature allows you to verify the authenticity, integrity, and publication date of all Docker images available on the Docker Hub Registry. This feature is not enabled by default but if you enable it by

export DOCKER_CONTENT_TRUST=1Docker notifies you, when you attempt to pull down an image that isn’t signed.

-

Run regular scans on your docker images for vulnerabilities. Vulnerability management is tricky because source images aren’t always patched. Even if you get the base layer up to date, you probably also have tens or hundreds of other components in your images that aren’t covered by the base layer package manager. Because the environment changes so frequently, traditional approaches to patch management are irrelevant. To stay in front of the problem you have to a) find vulnerabilities as part of the continuous integration (CI) process, and b) use quality gates to prevent the deployment of unsafe and non compliant images in the first place. Docker Hub has its own image scanning tool and there are paid options like Twistlock that provide image vulnerability analysis as well as a container security monitoring.

-

If needed, remove unwanted packages that your application does not depend upon with major and critical vulnerabilities from the base image to reduce the attack surface.